Nguni languages

| Nguni | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Southern Africa |

| Ethnicity | Nguni people |

| Linguistic classification | Niger–Congo? |

| Proto-language | Proto-Nguni |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | ngun1267 |

The Nguni languages are a group of Bantu languages spoken in southern Africa (mainly South Africa, Zimbabwe and Eswatini) by the Nguni people. Nguni languages include Xhosa, Zulu, Ndebele, and Swati. The appellation "Nguni" derives from the Nguni cattle type. Ngoni (see below) is an older, or a shifted, variant.

It is sometimes argued that the use of Nguni as a generic label suggests a historical monolithic unity of the people in question, where in fact the situation may have been more complex.[1] The linguistic use of the label (referring to a subgrouping of Bantu) is relatively stable.

From an English editorial perspective, the articles "a" and "an" are both used with "Nguni", but "a Nguni" is more frequent and more correct especially if "Nguni" is pronounced as it is suggested (/ŋˈɡuːni/)[by whom?].

Classification

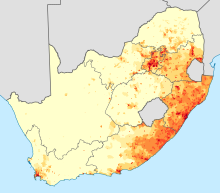

[edit]- 0–20%

- 20–40%

- 40–60%

- 60–80%

- 80–100%

Within a subset of Southern Bantu, the label "Nguni" is used both genetically (in the linguistic sense) and typologically (quite apart from any historical significance).

The Nguni languages are closely related, and in many instances different languages are mutually intelligible; in this way, Nguni languages might better be construed as a dialect continuum than as a cluster of separate languages. On more than one occasion, proposals have been put forward to create a unified standard Nguni language.[2][3]

In scholarly literature on southern African languages, the linguistic classificatory category "Nguni" is traditionally considered to subsume two subgroups: "Zunda Nguni" and "Tekela Nguni".[4][5] This division is based principally on the salient phonological distinction between corresponding coronal consonants: Zunda /z/ and Tekela /t/ (thus the native form of the name Swati and the better-known Zulu form Swazi), but there is a host of additional linguistic variables that enables a relatively straightforward division into these two substreams of Nguni.

Tekela languages

[edit]- Bhaca [6]

- Hlubi[7]

- Lala

- Nhlangwini

- Northern Transvaal Ndebele (Sumayela Ndebele)

- Phuthi [8]

- Swazi

Zunda languages

[edit]- Northern Ndebele (Zimbabwean Ndebele)

- Southern Ndebele (South African Ndebele)

- Xhosa

- Zulu

Note: Maho (2009) also lists S401 Old Mfengu†.

Characteristics

[edit]The following aspects of Nguni languages are typical:

- A 5-vowel system, by merging the near-close and close series of Proto-Bantu. (Phuthi has re-acquired a new series of superclose vowels from Sotho)

- Spreading of high tones to the antepenultimate syllable.

- A distinction between high and low tones on noun prefixes, indicating different grammatical roles, accompanied in some cases by an overt pre-prefix called the augment.

- Development of breathy-voiced consonants, acting as depressor consonants.

- Development of aspirated consonants.

- Development of click consonants.

Comparative data

[edit]

Compare the following sentences:

| Language | "I like your new sticks" |

|---|---|

| Zulu | Ngi-ya-zi-thanda izi-nduku z-akho ezin-tsha |

| Xhosa | Ndi-ya-zi-thanda ii-ntonga z-akho ezin-tsha |

| Northern Ndebele | Ngi-ya-zi-thanda i-ntonga z-akho ezin-tsha |

| Southern Ndebele | Ngi-ya-zi-thanda iin-ntonga z-akho ezi-tjha |

| Bhaca | Ndi-ya-ti-thsandza ii-ntfonga t-akho etin-tsha |

| Hlubi | Ng'ya-zi-thanda iin-duku z-akho ezintsha |

| Swazi | Ngi-ya-ti-tsandza ti-ntfonga t-akho letin-sha |

| Mpapa Phuthi | Gi-ya-ti-tshadza ti-tfoga t-akho leti-tjha |

| Sigxodo Phuthi | Gi-ya-ti-tshadza ti-tshoga t-akho leti-tjha |

Note: Xhosa ⟨tsh⟩ = Phuthi ⟨tjh⟩ = IPA [tʃʰ]; Phuthi ⟨tsh⟩ = [tsʰ]; Zulu ⟨sh⟩ = IPA [ʃ], but in the environment cited here /ʃ/ is "nasally permuted" to [tʃ]. Phuthi ⟨jh⟩ = breathy voiced [dʒʱ] = Xhosa, Zulu ⟨j⟩ (in the environment here following the nasal [n]). Zulu, Swazi, Hlubi ⟨ng⟩ = [ŋ].

| Language | "I understand only a little English" |

|---|---|

| Zulu | Ngisi-zwa ka-ncane isi-Ngisi |

| Xhosa | Ndisi-qonda ka-ncinci nje isi-Ngesi |

| Northern Ndebele | Ngisi-zwisisa ka-ncane isiKhiwa [9] |

| Southern Ndebele | Ngisi-zwisisa ka-ncani nje isi-Ngisi |

| Hlubi | Ng'si-visisisa ka-ncani nje isi-Ngisi |

| Swazi | Ngisiva ka-ncane nje si-Ngisi |

| Mpapa Phuthi | Gisi-visisa ka-nci të-jhë Si-kguwa |

| Sigxodo Phuthi | Gisi-visisa ka-ncinci të-jhë Si-kguwa |

Note: Phuthi ⟨kg⟩ = IPA [x].

See also

[edit]- Ngoni is the ethnonym and language name of a group living in Malawi, who are a geographically distant descendant of South African Nguni. Ngoni separated from all other Nguni languages subsequent to the massive political and social upheaval within southern Africa, the mfecane, lasting until the 1830s.

- IsiNgqumo is an argot spoken by the homosexuals of South Africa who speak Bantu languages; as opposed to Gayle, the argot spoken by South African homosexuals who speak Germanic languages. IsiNgqumo is based on an Nguni lexicon.

References

[edit]- ^ Wright 1987.

- ^ Eric P. Louw (1992). "Language and National Unity in a Post-Apartheid South Africa". Critical Arts.

- ^ Neville Alexander (1989). "Language Policy and National Unity in South Africa/Azania".

- ^ Doke 1954.

- ^ Ownby 1985.

- ^ Jordan 1942.

- ^ "Isizwe SamaHlubi: Submission to the Commission on Traditional Leadership Disputes and Claims: Draft 1" (PDF). July 2004. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ Donnelly 2009, p. 1–61.

- ^ www.northerndebele.blogspot.com[permanent dead link]

Bibliography

[edit]- Doke, Clement Martyn (1954). The Southern Bantu Languages. Handbook of African Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Donnelly, Simon (2009). Aspects of Tone and Voice in Phuthi (Doctoral dissertation). University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- Jordan, Archibald C. (1942). Some features of the phonetic and grammatical structure of Baca (Masters dissertation). University of Cape Town.

- Ownby, Caroline P. (1985). Early Nguni History: The Linguistic Evidence and Its Correlation with Archeology and Oral Tradition (Doctoral dissertation). University of California, Los Angeles.

- Wright, J. (1987). "Politics, ideology, and the invention of the 'nguni'". In Tom Lodge (ed.). Resistance and ideology in settler societies. pp. 96–118.

Further reading

[edit]- Shaw, E. M. and Davison, P. (1973) The Southern Nguni (series: Man in Southern Africa) South African Museum, Cape Town

- Ndlovu, Sambulo. 'Comparative Reconstruction of Proto-Nguni Phonology'